One Art

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

Elizabeth Bishop

Over the years, I reached a sort of detached attitude – which of course I lose regularly and annoyingly – towards the issue of loss. Losings bits and pieces of words, nuances, sounds, as if they were keys, or rivers, or distant friends.

But taking for granted that you do lose, I always prefer to think of what I gain.

I gain people, for instance: people that keep me company in a weird way, a bit like the imaginary creatures many of us talked to when we were kids. All the characters that, as if for magic, start talking in my mother tongue, stay with me for a while, with their clothes, their gaze, the way they walk, their voice.

I gain – one could say, steal – their stories, stories of marriages, war, birth, divorce, death, with all the relevant feelings: hate, affection, passion, suspicion.

I remember vividly, because I had to paint it in the colour of my language, the green dress of Annette, one of the characters of Dame Murdoch’s Flight of the Enchanter. I remember Julius in Teju Cole’s Open City, who gave me hints to find the right rhythm for sentences that had the slow steady pace of a pensive young man wondering and wandering in New York, with Mahler in the background.

I gain new words, made-up words for instance, like when I was forced to find a new vocabulary to describe the obscure instruments and diseases in Ben Marcus’ Flame Alphabet’

I gain memories of insignificant details I translate, like tiny photographs. An instagram diary of hands, windows, eyes, cups of coffee, gas stations, scissors, clothes. They captured my attention for their beauty and the fear of not being able to replicate it.

Small treasures, indeed, but they outnumber the losses.

I also gained huge treasures, whole geographies: I travelled all over the world in translation. Thousands of pages scattered in different continents. I tried to bring them home into a single language, to make them feel at ease in their new “Auberge du Lointain”, as linguist/poet/writer/translator Antoine Berman defined it.

I attempted to translate India many times, sounds pompous but it feels true. Not that spending so much of my real time in that endless country I grasped more of it. Yes, I lose when I have to translate even a banal word like tea stall. A tea stall or tea shop, (chaiwala in India, literally, tea man) is usually a makeshift table – it could be a bench or two wobbly planks of wood – where a gas stove is placed, and a delicious concoction of overly sweet tea, milk, and if you are lucky, cardamom, is brewed and served in small glasses or clay pots. How do you translate that into italian? Not with the equivalent of shop, nor with bancarella, which would be perfect for a vegetable stall.

So one day I found a solution, something like “baracchino del tè” which conveys the idea of a shaky, makeshift table, a jugaad table. Jugaad is another more or less untraslatable hindi word. It means something we know very well in Italy, and especially in Naples. The art of make-do, inventing, designing, coming up with ingenious solutions with very few means or instruments available.

But because I gained that word in my travels, reading and listening – and in this case seeing things created with the jugaad concept in mind – I had a clearer idea of how to translate ‘tea stall’.

You lose, you gain, renounce and add. Zigzagging, you get to the “best” solution – for you, for that book, in that precise moment of your life. Many other solutions could work as well, but it’s your language only, and the writer’s, so you are forced to accept your limits.

I lose, especially in Italian. Because Italian in my mind is like a shapely decadent lady in fine clothes and jewels, possibly from a decadent Roman aristocratic family, walking around slowly and haughtily. Italian is made up of plurisyllabic words. English is a skinny adolescent, skipping around town. Quick-paced, inventive, mono and bysillabic. You learn tricks to adjust them to each other.

I gained many other countries and cities the same way: whether I actually explored them or not (and I did most of the times), I was welcomed in their landscapes.

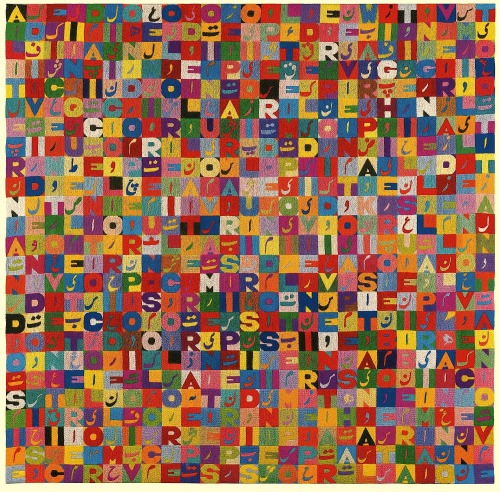

And because a translator usually learns to tread a narrow path between borders – author/translator, source language/target language, other tongues/mother tongue – I ended up creating an invisible mental map of this in-between territory. It’s a place I keep exploring, every day, sitting between two books, one completed, one in progress, carrying words and their layers of meaning from one to the other.

Over the years, after the initial fears and frustrations – “Poetry is what gets lost in translation!”, says Frost and Borges replies “The original is always unfaithful to the translation!” – I realized that I was getting better at using this very personal map of the in-between.

Now I don’t mind getting lost at all, in a new translation or in a new city. In general, I see it as a form of luxury, the freedom to wander about freely. And my map gives me a fine balance between taking endless decisions and humbly following somebody’s words and tracks.

Borderlines are territories of loss and stepping stones of nostalgia par excellence. At least in the realm of translation, the border is not made of violence and barriers, but of a peaceful coexistence of languages. Or at least this is what I like to think.

So, if we compare it with the losses of real life, we do lose very little with words, and it’s not at all a disaster. I can see my bejewelled Italian signora saying it while puffing away and sipping her cappuccino.

PS In Italian the translation of the movie title “Lost in Translation” is “L’amore tradotto”, i.e. “Translated love.”